How The Acolyte's penultimate episode honors "a certain point of view"

"Choices" fills in the gaps of what happened on Brendok, but adds to the complexity of the situation there.

I always sort of hated the moment in Return of the Jedi where Obi-Wan muses to Luke that what he originally told the young man about Vader was true “from a certain point of view.” Just admit you were lying to the kid to protect him, Kenobi! Just admit that you retconned that detail after you wrote A New Hope, George! Although maybe, in hindsight, that should have been my first hint that the Jedi were not always on the up-and-up.

But I’ve always sort of loved Obi-Wan’s follow-up to that: “You're going to find that many of the truths we cling to depend greatly on our own point of view.” It’s a reminder that the world is filtered by the lenses through which we see it. Our culture, our upbringing, our communities, and our biases all color what we ultimately see in others, and in ourselves.

It’s an evergreen sentiment. And if you wanted to put the theme that runs through the seventh episode of The Acolyte, and arguably the whole series, in a nutshell, I’d argue it comes down to that single face-saving statement from none other than Obi-Wan himself.

That idea comes through strongly in “Choice”, which presents the other half of the story told in “Destiny”, about the confrontation between the Jedi and the Brendok Coven that sparked the events of the series. There were a number of conspicuous gaps in what we witnessed in the prior episode. Before the season finale, The Acolyte takes pain to answer the important factual questions: about what set off the conflict at the Coven’s stronghold, about how the witches were decimated, and about what really happened with Mae starting that fateful fire.

But more than furnishing those plot points with added clarity, “Choice” recontextualizes what we saw earlier by recasting the events through the eyes of the Jedi, instead of through those of the witches.

Suddenly, the interlopers who would dare to try to steal children away from their family are, instead, caring crusaders who worry that the children might be being abused in some form or fashion. Seeming attempts to test the young ones as a prelude to their being taken away are, in reality, mere stalling tactics so the Jedi can receive official orders from the Council. And most importantly, neither group is the unified front of malign intent they seem to those on the other side.

I think that's my favorite part in all of this. Every group, every person here, contains multitudes. The Coven and the Jedi are not a case of good versus evil, or viciousness versus nobility. Both sides have those who are belligerent and those who are more accommodating, those who fear and judge their erstwhile antagonists and those who take a more measured approach to them . Both sides make understandable, if at times overzealous, moves to defend themselves or neutralize a perceived threat. And both sides bicker (or worse) within their own groups when it comes time to decide what to do about it.

Master Indara, a paragon of Jedi detachment, wants to play things by the book and avoid interfering with the Coven. Sol is more emotional and concerned for Mae and Osha’s wellbeing, with the lurking possibility that he might be blinded by an emotional attachment to them. For his part, Torbin is a young and brash padawan who just wants to complete this boring mission and get the hell back home. Each of them has a different idea about why they’re there, a different reaction to the presence of the Coven, and different thoughts about what their next move should be.

It’s a mirror of what we saw within the witches’ walls back in “Destiny”. Here, as there, Mother Aniseya and Mother Koril continue to argue for different approaches toward the Jedi. The Coven itself stands opposed to their leader over the question of whether to let Osha go with these impinging monks. Even the girls themselves, twin sisters and maybe more, are starkly different from one another in their personalities and desires.

At base, neither the Jedi nor the Coven are monoliths. There are complexities and disagreements inside each community that get flattened when viewed from the outside. Hell, there’s multitudes within each person here. Aniseya stands as both mother and leader, and Sol cuts the figure of both a centered Jedi Master and an emotionally affected human being. The ultimate reveal that this situation, and these people, are that much more complicated than we, or the characters themselves, believed, is a triumph in storytelling.

In the fullness of that complexity and with a broader view, the events of Brendok are exposed as a tragedy, not just for one side or another, but for everyone. The grim outcome on the planet is the result of a series of deliberate choices, certainly, but also a confluence of unfortunate accidents, of skewed reactions, of human frailties, that coalesce together into a wave of rampant regrets and senseless death.

Torbin is young and restless and thinks that finding the vergence within the witches’ stronghold is his ticket out of this dump. Mae is young and angry and made more so by a mother who feels she’s suffered mightily at the hands of the Jedi. So he starts a confrontation that ratchets up the tension on top of everyone’s preexisting mistrust. And she starts a fire meant to be small and symbolic that gets out of hand and ultimately destroys everything. The youthful impulses there, coming together to wreak havoc on everyone, are a metaphor for these events in micro and in macro.

Because these small, comprehensible decisions are what lead to a little girl pleading with her mother that something is terribly wrong. That's what leads to a parent aiming to use her abilities to try to help a child in grave danger. That's what leads to a concerned peacekeeper fearing he must stop an attack on a mistreated child. That's what leads to simmering tensions between two peoples at odds with one another erupting into full blown conflict. And in the throes of that conflict, a mistaken attack begets a furious defense, and provokes escalating assaults from both collectives that, in the end, leave the children both sides were trying to protect, without the parents to protect them.

There are no heroes or villains here, just complicated people, each with their own understandable interests, tripped up on mistrust and misunderstandings and their own personal hang-ups. Ultimately, it all swirls together into terror and tragedy. Both sides make mistakes. Both sides have their noble intentions and reasonable suspicions. Both sides lose a great deal in the process.

Oh yeah, and there’s some more frickin’ badass lightsaber fights.

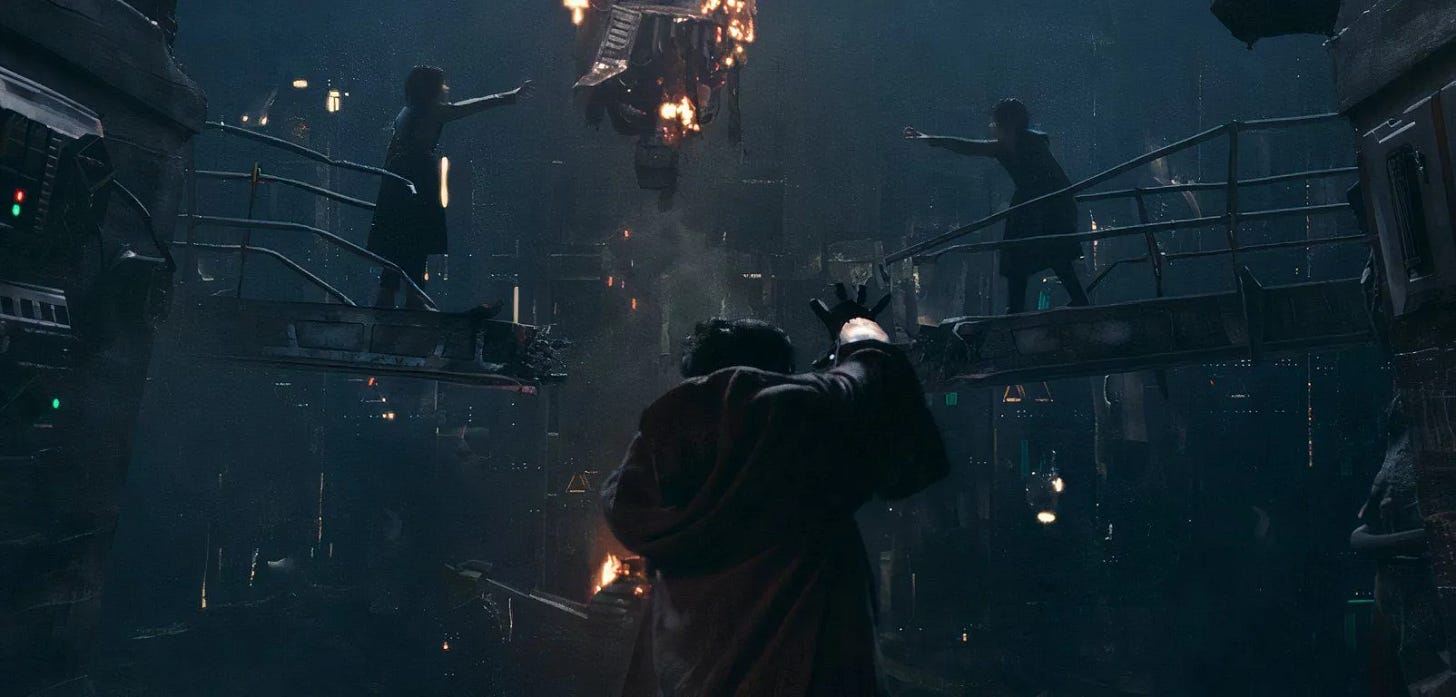

It’s hard to say why the battles we’ve seen on The Acolyte are so much more riveting and blood-pumping than many of the exciting but ephemeral ones across the Star Wars universe. It seems like the show’s directors and fight choreographers have taken an approach closer to good old fashioned Matrix-style wire fu rather than frantic but overblown fencing matches, an approach which tends to agree with me. But whatever the reason, it’s all a damn thrill.

As new Force-related powers go, watching Aniseya and Koril devolve into smoky wisps is creepy and cool in the best way. Watching the hum and sway of the Coven possessing one of their enemies and turning him against his own allies conveys the sense of their power and the uniqueness of their attacks in contrast to their enemies’ more physical assaults.

And my goodness, watching Torbin, Sol, and Indara have to fend off the brutish-yet-balletic attacks of a witch-addled Wookiee, while trying not to wound their friend, is absolutely incredible. The big set piece here, rife with cause and effect that builds and builds, that pays off so much growing tension, is cathartic in the action that bursts into the frame after so much of a lingering sense of a dam just about to break.

And yet, the most powerful moment comes in what sparks all of this, when Sol kills Aniseya mid-transformation and realizes that, unbeknownst to him, he was slaying someone who shared the same hope to protect those girls, rather than harm them. The grief on his face, Koril’s widowed fury, Sol’s resigned unwillingness to do more than offer a desultory defense in the shadow of his grave error, all sell the moment when the Jedi realize the horror of what they’ve wrought, and the hell that breaks loose in the aftermath.

Honestly, that's just scratching the surface of “Choice”. It’s easy to see Aniseya and Sol as kindred spirits, a desire to protect the same innocent children from the other unwittingly uniting them before it cleaves everything apart. But holy hell, Aniseya’s “Would you like to live deliciously?”-style temptation of Torbin in the name of gaining a bargaining chip against the Jedi plays like a truly devilish manipulation on her part.

Likewise, Indara goes from being the invading interloper to being the voice of caution and restraint. The way she presents a unified front to the Coven, but in her own camp, is asking age-appropriate questions of Mae to check for abuse, chastens Sol over his emotions interfering with his judgment, and basically tries to hold back her crew from intervening at all, paint a very different picture of her than the one the witches saw. Once more, showing us more depth and complexity within the situation is never a bad thing.

So even when Indara nearly loses her cool with Sol, in the aftermath when she, who’s preached such restraint, doesn’t want to rob Osha of more than she’s already lost, when she’s the one who offers a lie of omission, it carries weight, and adds even more complexity to the situation. It completes the picture for the audience, but not in a way that makes the answers feel rote or mechanical. Instead, we see a broader tapestry of choices, each made for comprehensible and personal reasons, that nonetheless add up to disaster.

You can argue about each individual choice made by every person involved in this situation. Plenty made mistakes. Plenty of those errors came from flattening the other side into something that fit your preconceived notions about them. Plenty came from assuming the worst based on incomplete information. The lesson seems to be less about who’s good and who’s bad, and more about the tragedies that unfold in the wake of two groups only seeing glimpses of one another, and folding those into their understandable but ungenerous assumptions about each side, until things have gone too far.

But everyone in that struggle had their reasons. Everyone involved had their understandable motivations, born of their past experiences and personal issues. Everyone thought they were doing the right thing. And maybe they were, from a certain point of view.